Conditionals

Conditionals will allow our programs to make choices rather than always doing exactly the same sequence of statements. The most common conditional is if, which can be used to choose whether or not to do a sequence of statements in the code, and is sometimes used with else, to choose between doing one or the other of two sequences. A conditional will check a boolean value and do one thing if the value is true, something else (possibly nothing) if the value is false.

Booleans

The boolean type to is used to store data about whether something is true or false. Under the hood, we can use a single binary bit to store off/on to represent 0/1 or false/true.

We will write the possible literal values of booleans as false and true.

In some cases, we would create a boolean variable and set its value directly to establish whether something is true

boolean dogCanFly = true // magic dog, yay!

boolean movie_is_scary = false

However, it is very common for booleans to get their values from expressions instead of being directly set like this.

Booleans only have the two possible values true and false, which are opposites. To talk about opposites, we say "NOT" which is often written with an exclamation point. So NOT true is false and NOT false is true, usually written as !true == false and !false == true. ! is an example of a logical operator, an operator that can act on the value of a boolean.

Boolean Expressions – Relational Operators

A boolean expression is an expression that is evaluated and

comes out as a single true or false value. Boolean expressions are usually

written using relational operators to check for equality, greater than,

less than, etc. We can also combine

multiple boolean values in more complex expressions.

A relational operator is used in an expression between two values of the same type, and this expression evaluates to either true or false. Our standard relational operators are

|

operator |

Called |

true when |

|

a == b |

“equals equals” |

a and b hold same value |

|

a !=

b |

“not equals” |

a and b hold different values |

|

a > b |

“greater than” |

a holds a larger value than b |

|

a < b |

“less than” |

a holds a smaller value than b |

|

a >= b |

“greater than or equal to” |

a holds a value larger or same as b |

|

a <= b |

“less than or equal to” |

a holds a value smaller or same as b |

Note that each expression has an opposite – our NOT again -- which is true when it is false and false when it is true. We even incorporate the exclamation point into the syntax: a == b is true when a != b is false and false when it is true. The opposite of a > b is a <= b and the opposite of a < b is a >= b.

If

the if structure uses a boolean to determine whether or not to execute a sequence of statements in code. An if is always looking for its boolean to be true. Our syntax of If looks like

if (boolean condition) {

// code to do only if the condition is true

}

We are using curly braces to delineate the beginnings and endings of structures in our pseudocode. The part inside the curly braces is called the body of the if, which we often casually call “in the if.” In the body of the if you could put any code that you could have anywhere else in a method – create variables, do operations, print, whatever.

The condition in the parens of the if must evaluate to a boolean value. In the case that boolean comes out true, we will run all statements inside the body of the if. But when the boolean comes out false, we will skip all of that and jump to the next statement after the end curly of the if. Booleans have no third options.

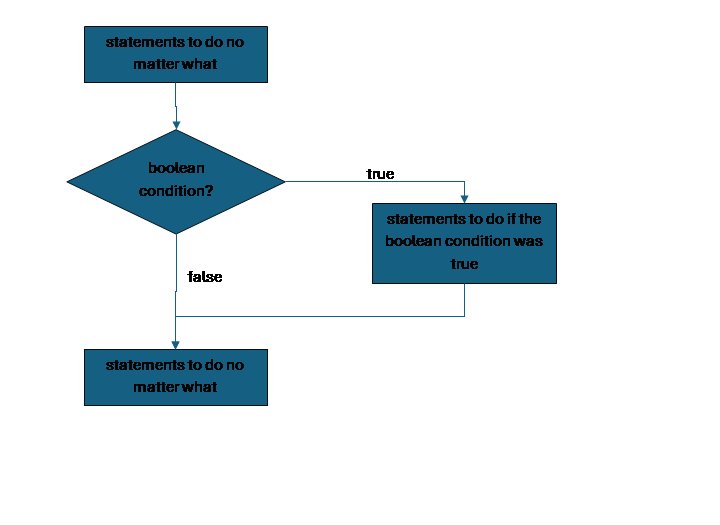

We could represent this if with the flowchart:

The condition in the parentheses of the if could be a single boolean variable, but is most often a boolean expression.

For example, if we already have variables for whether a submission was late, for a fee, and for a current balance, and we are deducting a fee from the balance as a penalty for late submissions, we could say:

if (submissionLate) {

print("Late Penalty: $" + fee)

funds = funds – fee

}

Either the submission was late or not, so submissionLate is either true or false. If it is true, we will print a message and deduct the fee, otherwise we will skip those statements and go on with whatever is next in the program.

Another example: if we already have variables ponyPrice and funds, and we want to celebrate buying a pony and pay for it if our funds are high enough to afford the pony’s price, we could write

if (ponyPrice <= funds) {

print("Buying a pony yay!")

funds = funds – ponyPrice;

}

Either the ponyPrice is less than or equal to our current funds, or not, so this expression will evaluate to either true or false. If true, we will print and subtract the price from the fund, if false, the program will skip those two statements.

If by itself is appropriate

in the case when we have a sequence of steps that we either want to do or

skip. This commonly happens if we have

code that we want to do, but some

requirement needs to be met (we have enough money to buy a pony) or if we have

code that we only have to do if there is some problem (make the user pay a fee

if their submission is late).

If always looks for its condition to be true. We can adjust how we write the condition to fit with this. Suppose instead of imposing a fee for late submissions, we want to celebrate those that aren’t late. We can use our logical operator NOT to adjust for this, to check for the opposite of lateness being true:

if (! submissionLate) {

print("Thank you for submitting on time!”)

}

If Else

In many cases when our

programs make choices, we arent just choosing whether or not to do something,

we instead have two options, and we want to do one or the other. In that case we would pair the if with an

else. Now we will have one sequence of

statements in the if, and another sequence of statement in the else.

The else is always checking the same condition as the if, but while the if is checking for true, the else is always checking for false. Since any boolean expression will always come out to one or the other, either the if or the else will win. Whichever one wins, we do those statements and skip the others. We would never have else without if.

if (condition) {

//statements to do if the condition is true

//“body of the if”

} else {

// statements to do if the condition is false

// “body of the else”

}

Notice that since the else is just a partner to the if, we usually write it right on the same line as the end curly of the if.

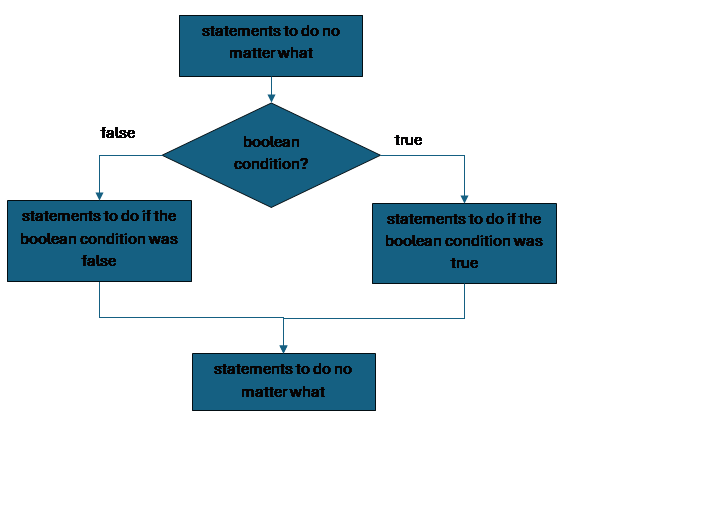

To visualize this:

Let’s decide that if we cannot afford a pony, we will go to work to make more money. We might say something like

if (ponyPrice <= funds) {

print("Buying a pony yay!")

funds = funds – ponyPrice

} else {

print(“No pony today! Back to work.”)

funds = funds + wages

}

Now, if the condition comes out true we will do the two lines in the if, but skip the else, and if the condition comes out false, we will skip the two lines inside the if and do the else instead.

If always checks for true and else always checks for false, so we could always change the condition and do them in the other order:

if (ponyPrice > funds) {

print(“No pony today! Back to work.”)

funds = funds + wages

} else {

print("Buying a pony yay!")

funds = funds – ponyPrice

}

This has exactly the same result as the previous, since we swapped the condition to the opposite, but also swapped contents of the if and else bodies.

We often choose to write if-else with what we think is the more likely, or preferable, case in the if position.

Common Errors

When students are first learning conditionals, they often think they always need a relational operator, even when working with something that is already a boolean, so they stick in == true. Although this doesn’t cause an error in most languages, it’s pointless, adding an extra step for no reason.

// suppose we already have ints x and y and boolean b1 and b2

// extra step:

if ((x == y) == true)

// correct:

if (x == y) {

print(“Same ints”)

}

//extra step:

if (b1 == true)

//correct:

if (b1) {

print(“yes b1”)

}

// extra step:

if ((b1 == b2) == true)

// correct:

if (b1 == b2) {

print(“Same bools”)

}

Having an == false in a condition is also not an error, but it is generally not how a programmer would write the code, they would use ! instead.

// suppose we already have ints x and y and boolean b1 and b2

// awkward:

if ((x == y) == false)

// correct:

if (x != y) {

print(“Different ints”)

}

// awkward:

if (b1 == false)

// correct

if (!b1) {

print(“no b1”)

}

// awkward:

if ((b1 == b2) == false)

// correct

if (b1 != b2) {

print(“Different bools”)

}

When we only have one option, then we only need if without else (it’s an error to try to have else without if). This is right even if the thing we’re checking for is something we think of as false.

// suppose we already have ints x and y and boolean b1 and b2

// NO! don’t use else with empty if!

if (x < y) {

} else {

print(“x not less”)

}

// YES, one option, just if

// could also write condition as (x >= y)

if (! (x < y)) {

print(“x not less”)

}

In our pseudocode, as in many real languages, we use one equals sign for assignment, but two equals signs to check equality. Watch out for accidentally making a typo here; in some languages, it is technically legal to put an assignment inside the condition of an if, as long as it is assigning a boolean variable, but this not what we wanted!

// suppose b1 and b2 are booleans

// single = is assignment, not checking equality

if (b1 = b2) {

print(“oops!”)

}

If this is legal, it is not checking whether b1 and b2 are the same, it is changing b1 to be the same as b2!

Nesting Conditionals

We can have any code inside the body of a conditional (if or else) that we would have anywhere else in code, including more conditionals, so we could have an if-else inside an if or an if inside an else (remember that we never have an else without an if). This allows us to say that we will only check for something in the case that we have already checked for something else.

Here is an example that covers checking all combinations of two conditions.

if (first_condition) {

//statements here only depend on first being true

if (second_condition) {

// do if both are true

} else {

// do if first is true but second is false

}

// statements here only depend on first being true

} else {

// statements here only depend on first being false

if (second_condition) {

// do if first is false but second is true

} else {

//do if both are false

}

//statements here only depend on first being false

}

Notice that there is only one structure checking first_condition, which we would call the “big if-else” or the “outer if-else” but there are two separate structures checking second_condition, which we might call the “small if-elses” or “inner if-elses”. Also notice that there is space here for code that is inside the body of the big if-else but not inside the small if-else, where we can put code that only depends on the first condition.

else if

It is very common to have a series of possible conditions or values we need to check, with a different behavior for each. We would check for the first one, then if that fails check the next, and so on. In that case, we could write a deep nesting of if-else structures:

if (first_condition) {

//behavior for first condition

} else {

if (second_condition) {

//behavior for second condition

} else {

if (third_condition) {

//behavior for third condition

} else {

//behavior if none of those conditions holds

}

}

}

This works, but writing it in this way implies that the first condition is the most important, and each subsequent condition is less important or less likely. If they are simply a set of equally important and likely options, we would usually simplify the code by writing an else with an if immediately after it, on the same line:

if (first_condition) {

//behavior for first condition

} else if (second_condition) {

//behavior for second condition

} else if (third_condition) {

// behavior for third condition

} else {

// behavior if none of those conditions holds

}

This visually implies that while we chose to check first-condition first, these options are roughly at the same level or importance or likelihood. It is also shorter and most people find it easier to read.

Notice that this example ends with an else, not a last if. So if none of the conditions we checked for holds, we will do the else.

If instead we ended with an else + if, then there would be the possibility that we would do nothing at all for this code, if nothing including that last if’s condition turned out true. Sometimes that is what we want

if (x < 10) {

print(“negative or one digit number”)

} else if (x < 100) {

print( “two digit number”)

} else if (x < 1000) {

print( “three digit number”)

}

// when x is >= 1000 we just don’t do anything

If the conditions are totally separate issues we are checking for, then ending in an else-if makes sense if we know that sometimes none of those situations holds so we have no actions to take. If the conditions are related and together cover all possibilities, we almost certainly want to end with an else which covers the last possibility.

Case / Switch Statement

When we have a list of mutually exclusive situations that

depend on specific values of a single variable, we have a special conditional

structure called a case, or switch statement.

In a case statement, we say which variable we are checking, and then

list out some values, and then the code that we want to execute for each value,

until we have listed them all, possibly with an extra case for default, to

cover all other possible values, and then close with endcase.

case variableName {

value1 :

statements to do if variableName has value1

value2 :

statements to do if variableName has value2

value3 :

statements to do if variableName has value3

default: statements to do for

all other values of variableName

}

In this pseudocode, we are assuming that whichever value we

match, we would run only the statements for that value, and then the case

statement would end and go on with the rest of the program, in the same way

that if we run the body of an if, we then skip the else.

In many languages, there is a version of the case statement

with fallthrough.

This is sometimes called switch, although “case” and “switch” are also

often used interchangeably. Fallthrough means that we use a special keyword, usually

break, at the end of each case to end the structure there, but otherwise we

fall through from the code for that value and continue with the code for the

following values.

switch variableName {

value1 :

statements to do if variableName has value1

value2 :

statements to do if variableName has value2

but also do these after the code for value1

break

value3 :

statements to do if variableName has value3

default: statements to do for

all other values of variableName

but also do this after the code for value3

break

}

Since there was no break after the value1 case, after we

were finished with the statements for value1 we would continue with those for

value2; however value2 has a break, so after that we

would stop and leave the switch. Since

there is no break after value3, for that value we would do the value3 specific code, but then continue on to do

the code in the default case. Since the

default case is at the end, we would stop and leave the switch then anyway, but

it is common to still put a last break it not make this

explicit (and in some languages this is required).

Case statements were very common in programs that had menus

where the user was given a list of options and entered a number to choose what

they wanted to do. We could do a case

statement based on the variable we read in from the user and put each behavior

next to the value the user entered, plus have the default case to tell them if

they entered an invalid answer. This

kind of program is much less common now except in kiosk situations like gas

pumps, but case statements are still useful if we have a limited list of values

and a behavior for each.

Notice that we cannot use case statements to handle ranges of values. if we have the same behavior for all values from 1 to 10, we would have to type an individual case for each one. in such situations, it would be easier to use if-elseif instead. If we really need the fallthrough of a switch for some reason, but we start off with ranges, we could use if-elseif to set a new variable to one of a list of values, and then use that to enter the switch.

Boolean Expressions – Logical Operators

We use logical operators to combine multiple booleans, for instance requiring that two booleans are true at the same time.

Our standard logical operators are

|

operator |

called |

true when |

|

!p |

NOT |

p is false |

|

a && b |

AND |

both a and b are true |

|

a || b |

OR |

a is true or b is true or both are true |

We use NOT to swap between true and false. NOT in front of a false value comes out true, and NOT in front of a true value comes out false.

We use AND when we want two things to be true at the same time. We use OR when we need at least one of two things to be true.

These operators give us the ability to combine multiple requirements that we want to check, all in a single boolean expression.

Truth tables are one way of seeing the behavior of an expression with logical operators. A truth table lays out a row for each possible combination of the individual booleans involved and then shows how the whole expression comes out. Here is the truth table for NOT

|

a |

! a |

|

true |

false |

|

false |

true |

Since NOT only acts on one boolean, it is a very small table, just showing that the outcome of using a NOT is the opposite of the value started with.

Here is the truth table for &&:

|

a |

b |

a && b |

|

false |

false |

false |

|

false |

true |

false |

|

true |

false |

false |

|

true |

true |

true |

The table shows that an && expression is false in every case except where both elements are true at the same time.

Here is the truth table for ||:

|

a |

b |

a || b |

|

false |

false |

false |

|

false |

true |

true |

|

true |

false |

true |

|

true |

true |

true |

The table shows than an || expression is true in every case except where both elements are false.

if (age >=0 && age < 18) {

} else if (x < 65) {

print(“adult ticket”)

} else if (x < 150) {

print(“senior discount”);

} else { // means x is in none of the above categories

print( “invalid age, check ID”)

}

We earlier had code to check for all combinations of two conditions. If we want to check for two conditions at the same time, we could also use our logical operators. Here is code to check for all possible combinations of two booleans, using if-else-if structure:

if (first_condition && second_condition) {

print("both are true")

} else if (first_condition) {

print("first is true, second is false")

} else if (second_condition) {

print("first is false, second is true")

} else {

print("both false")

}

Note that we didn’t have to check for first_condition AND NOT second_condition for the case where first is true and second is false: if both were true, we would have stopped in the first if, so we know at least one is false when we get to the first else-if. So if we check first_condition and it is true, then it must have been second_condition that was false. Same holds for the second else-if. The last else doesn’t need to check for them both being false; again, if we know we are covering all possible cases, we can just end with an else to cover the only case we haven’t checked yet. So this would be silly and redundant:

if (condition1) {

if (condition1 && condition2) {

print("both are true")

} else if (condition1 && !condition2){

print("first is true, second is false")

}

} else if (!condition1){

if (!condition1 && condition2) {

print("first is false, second is true")

} else if (!condition1 && !condition2){

print("both false")

}

}

So that means this would be equally silly and redundant.

if (age >=0 && age < 18) {

print(“child ticket”)

} else if (age >= 18 && x < 65) {

print(“adult ticket”)

} else if (x >= 65 && x < 150) {

print(“senior discount”)

} else if (x < 0 || x >= 150) {

print( “invalid age, check ID”)

}

deMorgan’s Laws

When writing longer boolean expressions it is important to know how these operators interact. The most important rules are deMorgan’s laws about the interaction between ! and && and ||. The overall guideline is that a NOT in front of another operator can be distributed to each operand, and then swaps the operators between && and ||.

So,

! (a && b)

is the same as

(! a || ! b).

This should make sense if you think about ! meaning the opposite: the opposite of “both of these are true” is “at least one of these are false.”

Similarly,

! (a || b)

is the same as

(! a && ! b).

This should also make sense: the opposite of “at least one of these is true” is “both of these are false”

deMorgan’s laws are often useful when you can easily describe the situation you don’t want, but you are using a tool like an if that checks its condition for true, so we need to write accordingly.

If I have actions to do, but I can’t do them if it is above 90 degrees and there are any raccoons present, I might think of it as (temp > 90 && raccoon_count >0) but actually, I want to check not for this bad case, but for the opposite. So the good case is

! (temp > 90 && raccoon_count >0)

We can re-write this using deMorgan’s laws as

! (temp > 90) || ! (raccoon_count >0)

If we think about how relational operators work, the opposite of > is <=, so this can also become

temp <= 90 || raccoon_count <= 0

Note that all of these ways of writing the condition are legal and valid. We should choose the one that most clearly expresses the way we are thinking about the situation.